There are few things cuter than a wholesome die-hard Indian bromance. In the past decade, the term “bromance” has become popularized by the American media and by high-grossing summer flicks that explore its comedic aspects—but its roots can be traced back to Hollywood first academy award for best picture Wings (1927). This silent heart-wrenching World War I love-fest between two men inspired dozens of commercial hits down the road from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) to Top Gun (1986). Say what you want about those films, however, Bollywood was unarguably where this concept blossomed to its colorful fullest.

Perhaps it’s cultural—I can remember visiting Simla when I was younger and seeing teenage boys holding hands as they walked down the street. It was just considered a normal expression of friendship. Things have changed plenty since my childhood, but regardless, the marketability of the bromance genre may also likely stem from what had (and has) been for a long time a male-dominated industry–from directors to screenwriters all the way down to the lowly production assistants. In fact, in the early pre-talkie years of Indian cinema, women were not even allowed to act in films, much less attend viewings. Y-chromosome melodrama sells, and sells big. The bonds of manly love have been a glorified subject of Bollywood expression since time immemorial and has inspired some of the best movies you’ll ever watch.

In this post, we’ll explore our top 5 “bromantic” songs of yesteryear films long before the days of Dostana (2008) and even Qurbani (1980). From declaring eternal devotion to sobbing over betrayal, each one has a special place in our hearts and cinematic history.

Yeh Dosti (Sholay 1975):

This song is the crowning jewel of Bollywood bromance. Set at the beginning of an all-time megahit, this song showcases two men (Amitabh Bachhan and Dharmendra) riding a single motorcycle and singing their love for each other. Chest-hair is just blowing in the wind as their friendship is put to the test at the film’s climax. Overdone slightly, but a timeless tear-jerker!

Dost Dost Na Raha (Sangam 1964):

Talk about tragedy. Raj Kapoor flies to war and saves his country, only to return and discover that his wife Vijayantimala is really in love with his own best friend Rajendra Kumar. This song of betrayal and lost friendship played morosely on the living room piano makes everyone in the room awkward. Please note that low-cut v-neck top. No, I’m not referring to Vijayantimala.

Diye Jalte Hai.N (Namak Haraam 1973):

A Rajesh Khanna classic. Although best friends, Rajesh Khanna and Amitabh Bachhan come from two very different socio-economic statuses, ultimately leading to a huge public morally-charged battle of principles. Rajesh Khanna plays the good guy as usual, and his on-screen chemistry with Bachhan evokes the joy audiences loved in Anand! Did I mention the obligatory and visible fluffy chest hair?

Chahoonga Mai.N Tujhe (Dosti 1964):

This film was unique in that it is entirely about two teenage boys (neither of whom were big stars then) and the sacrifices they make for each other. Did I mention the hero is blind and homeless? It makes it more endearing. This beautiful Mohammed Rafi song of tragedy is when the hero realizes his best friend is better off without him, and decides to get out of his way forever. These are kids, guys. It’s really, really cute.

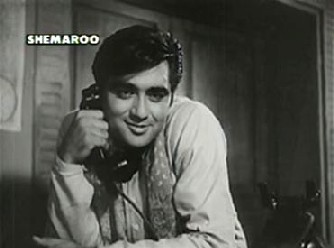

Pran works to get a smile out of Amitabh Bachhan in Zanjeer (1973). This is a must-see–Pran is just such a beast in this movie.

Yaari Hai Imaan Mera (Zanjeer 1973):

Oh, Pran, you are a legend. This famous song celebrates the friendship between an Indian (Amitabh Bacchan) and an Afghani patthan (the inimitable Pran). He embodies this character so skillfully—look at how he twirls and gives that sly shake of the head, you’d think he had grown up in a mountainous outskirt of Kabul. See, Bollywood knows how to cross political boundaries too!

An extremely honorable mention goes to “Anhoni Ko Honi” from Amar Akbar Anthony (1979). Does it really count as a bromance if they’re actually supposed to be brothers?

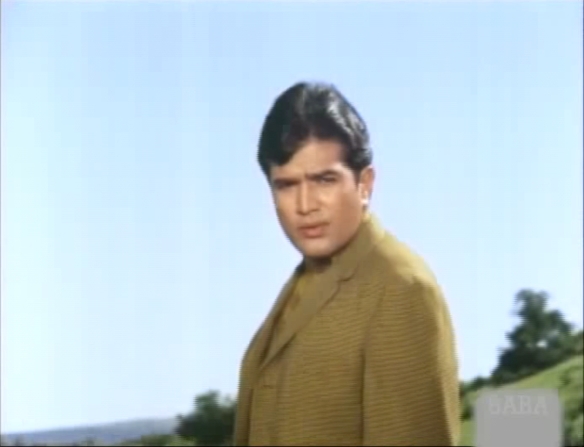

Amitabh Bacchan, Vinod Khanna, and Rishi Kapoor are three brothers on a mission in Amar Akbar Anthony (1979)

Share with us your thoughts and additions to our list!

-Mrs. 55