Meera-bai (c. 1498-1547 A.D) was a mystical poet and devotee of Lord Krishna

When most people think of Bollywood cinema, they usually think of extravagant costumes, seductive dance moves, and lots of melodramatic overacting. While all this extravagance is certainly an integral aspect of the industry, you may be surprised to learn about a saintlier side of Bollywood that I will discuss here today: the use of Meera-bai’s texts in Hindi film music.

Meera-bai was a 16th-century mystic whose devotion to Lord Krishna has been immortalized in Indian culture through her poetry and bhajans (religious songs). Meera, a Rajput princess, was married off to a prince at young age, but this marriage did not satisfy her as she already considered herself the spouse of Lord Krishna. Her husband died in battle soon after their marriage and Meera became a widow at an early age. Meera transformed her grief into spiritual devotion and wrote many poems in praise of Lord Krishna. In her texts, she worships Krishna from the perspective of a lover longing for union: romantic on one level and spiritual on another. Although her undying devotion to Krishna was initially a private matter, public moments of spiritual ecstasy soon outed her to society. Eventually, her brother-in-law became displeased with her excessive devotion for Krishna and made several attempts on Meera’s life. The most well-known story describes how he poisoned Meera’s prasad and made her drink it, but the Lord transformed the poison into amrit (spiritual nectar) to save her life.

Meera-bai’s texts express themes that are highly pertinent to heroines in Hindi cinema from the Golden Era. Interpreting and contextualizing Meera’s love for Lord Krishna can be a challenging task, however, because of its apparently paradoxical relationship to acceptable gender norms for women at the time. On one hand, Meera could be considered the ideal Indian woman for the eternal devotion she displays toward her lover–in this case, Lord Krishna–in spite of all the obstacles placed in her way. The type of selfless devotion and sacrifice Meera-bai displays toward Krishna is the same type of devotion that Indian women in the chauvinistic climate of the ’50s and ’60s were expected to provide their husbands. On the other hand, Meera-bai actually subverts the typical pativrata norms established by Indian society because her devotion is misplaced. Instead of serving her human husband, Meera devotes all of her love to Krishna, which is inconsistent with society’s expectations for the dutiful and virtuous Indian wife. This is further complicated by the fact that Meera, in her mind, actually considered herself to be the wife of Krishna (and supposedly conducted a marriage ceremony with a Krishna idol at a temple).

In any case, it is undeniable that Meera’s texts contain universal themes about love, pain, and devotion that have permeated several mediums of the South Asian cultural sphere. Here, let’s analyze a couple of examples in order to see how Meera’s words have been used in the context of Hindi film songs:

pag ghungruu bandh miiraa nachii re (Meera, 1947): Meera (1947) is a rare treat for lovers of Bollywood films because it is the only Hindi film ever made that features M.S. Subbulakshmi as both an actress and playback singer. M.S. Subbulakshmi, who was the first musician to be awarded the prestigious Bharat Ratna, is one of the most renowned vocalists in the history of the Carnatic musical tradition. Her singing is ethereal and sublime, and many people have praised her by saying she is modern-day personification of Meera-bai herself! Although she retired from films early in her career to pursue classical concert music, her portrayal of Meera in this film is remembered to this day for its natural and pure expression of spiritual divinity. Words don’t do this woman justice, so just click the link and take a listen for yourself. I’ve selected one of about 20 Meera bhajans that are found in the film; in this particular poem, Meera uses the metaphor of dance to describe her love for the Lord. You may have noticed that the first line of this bhajan was used in another (much less saintly) Bollywood classic rendered by Kishore Kumar and composed by Bappi Lahiri from Namak Halaal (1982) decades later.

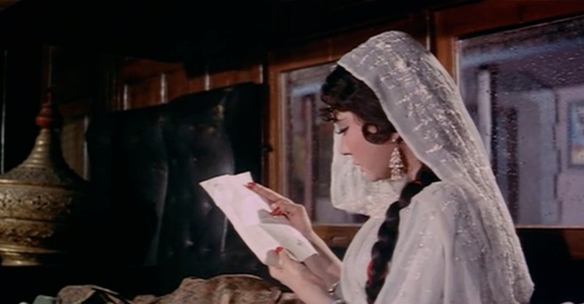

M.S. Subbulakshmi embodies the spiritual divinity of Meera-bai in the 1947 Hindi remake of the Tamil film Meera.

ghunghaT ke paT khol re, tohe piiyaa mile.nge (Jogan, 1950): I have always thought that one of Geeta Dutt’s strengths as a singer was her rendition of bhajans. She shines here in this Raga Jaunpuri-based devotional composed by Bulo C Rani that has some beautiful words penned by Meera-bai. Literally, the first line translates roughly as “remove your veil so that you can get a glimpse of your beloved.” However, on a deeper level, Meera-bai is using the veil as a metaphor for ignorance–she is asking us to remove our veils of ignorance so that we can be closer to the Lord.

erii mai.n to prem divaanii, meraa dard na jaane koii (Nau Bahar, 1952): Lata Mangeshkar is brilliant in her rendition of this Raga Bhimpalasi-based bhajan composed by Roshan and picturized on Nalini Jaywant in Nau Bahar. Inspired by a Meera-bai poem, the words here describe how Meera’s devotion to the Lord can is best expressed through love, as she is unfamiliar with the traditional rites and rituals of worship.

jo tum toDo piiyaa, mai.n naahii.n toDuu.n (Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje, 1955): V. Shantaram’s Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje was one of India’s first technicolor films when it was released in 1955. In this Filmfare award-winning film, when the character played by Sandhya fears that she has destroyed her beloved’s (played by Gopi Krishna) dancing career, she becomes so depressed that she decides to reject all wordly pleasures and become an ascetic like Meera-bai. This Bhairavi-based bhajan composed by Vasant Desai is rendered beautifully once again by Lata, who succeeds in expressing the sentiment of Meera’s words about unconditional devotion to her Lord even if he is not faithful to her.

piyaa ko milan kaise hoye rii, mai.n jaanuu.n naahii.n (Andolan, 1977): Asha Bhonsle tends to employ a lot of over-the-top histrionics in her songs, but music director Jaidev manages to get Asha at her pure, unadulterated best with this soulful composition from Andolan picturized on Neetu Singh.

mere to giriidhhar gopaal, duusro na koii (Meera, 1979): Directed by lyricist Gulzar, this film is yet another Bollywood biopic about Meera-bai, and Hema Malini takes the starring role here. Despite high hopes, this film achieved only moderate success at the box office. However, the film’s soundtrack of compositions by sitar virtuoso Pandit Ravi Shankar has certainly left a memorable legacy. In this particular poem, Meera-bai’s words express her singular devotion to the Lord; there is no one else in the world for her except for her Lord Krishna. While Hema falls a little flat in her portrayal of Meera, Vani Jairam actually does a great job expressing the appropriate emotions needed in this rendition and in the rest of the songs on the soundtrack. However, as you may have suspected, Vani was not Ravi Shankar’s first choice of singer for this film–his first choice was none other than Lata Mangeshkar. Lata, however, turned him down, by using the following reasoning:

“How could I? I had already done Meera bhajans for my brother Hridaynath.”

Now, don’t get me wrong, I love the non-filmi album of Meera bhajans released by Lata and Hridaynath. In fact, Lata’s rendition of a similar text “mhara re giridhhar gopaal, duusra na koii” tuned by Hridaynath for this album is absolutely exquisite. However, her reasoning here doesn’t really make sense to me. Even before her album for Hridaynath, Lata had sung plenty of Meera bhajans for films (see above!) under the baton of other music directors, so I don’t see how this excuse constitutes a legitimate reason to refuse singing in this film. I suspect that her refusal had more to do with some lingering bad blood between her and Ravi Shankar from their prior collaboration on Anuradha (1960): apparently, tensions had flared between the two of them because Lata had failed to show up to a recording session of “saa.nvare saa.nvare” without prior notice.