I feel like we’ve all been in this situation at some point: one of your favorite aunties steps up to the microphone at the annual Diwali function, and you have a sinking fear in your heart that she’s going to embarass herself by butchering another Lata classsic on stage. As she struggles through the sky-high notes of the antara, you cringe and ask yourself why you’re here again, subjecting yourself to this torture…

Well, it turns out it’s not entirely her fault. The reality of the situation is that Bollywood songs from the Golden Era tend to be pitched at extremely high scales for the average female singer. Unless a woman is a veritable soprano like Lata Mangeshkar or Asha Bhonsle, it is going to be quite a challenge for them to sing many of the classic songs from this period in their original keys. The high-pitched soprano female voice has become a hallmark of Hindi film music, and I’d like to explore this phenomenon in greater detail with this post.

Two sisters who changed playback singing forever: Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhonsle.

Why are Bollywood songs for females from the Golden Era pitched at astronomically high scales? I don’t know for sure, but I definitely have a few ideas that could explain this trend. First, the high-pitched female voice is consistent with the image of the ideal Indian woman that was prevalent during the 1950s and 60s. The soprano register suggests innocence and purity, which enhanced the traditionally feminine perceptions of heroines advanced by film directors of the time. Lata Mangeshkar is the ultimate example of this phenomenon; her voice, with its ethereal purity, has been considered the traditional female voice of India for decades. However, this explanation is less pertinent to Lata’s younger sister Asha Bhonsle. The voice of Asha, who was widely known for her experimentation with non-traditional genres such as the cabaret, is not a national emblem of purity in the same way as her elder sister’s. For this reason, an alternative explanation is needed to describe the popularity of the soprano female voice in Bollywood, and I would venture to say that this alternative explanation is rooted in musical origins. Before the arrival of the Mangeshkars onto the filmi musical scene, female singing in Hindi films was dominated by artists with heavy, nasal voices, such as Suraiyya and Shamshad Begum. Once music directors had the opportunity to work with the Mangeshkars, things changed forever: the nasalized heavy female voices were out and the delicate soprano voices were here to stay. After Lata and Asha became established as playback singers, I would argue that music directors of the time pushed the boundaries of their compositions in terms of range to test and showcase the virtuosity of these two exceptional talents.

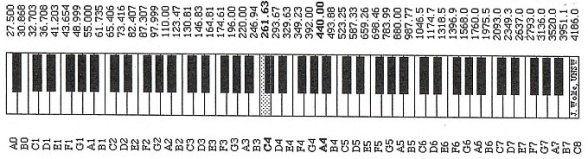

Before we take a listen to some of Lata and Asha’s highest highs throughout Bollywood’s musical history, explaining a little bit of musical nitty-gritty is necessary to fully appreciate the gist of what’s going on here. From my experiences with transcribing and performing many songs from this era, I would estimate that the vast majority (perhaps 90%?) of songs composed for Lata and Asha max out at F5 or F#5 (two F/F#’s above middle C on the piano) as their highest note. Therefore, in the brief list of high notes that I’ve compiled below, I’ve only chosen to include those rare songs that surpass the typical upper limit of F#5. Songs for both singers are listed in order of ascending pitch of the composition’s highest note.

Keyboard labeled with note names and frequencies. C4 is taken as middle C. The high notes listed here range from G5 to C6.

Lata Mangeshkar: Selected High Notes

jhuumta mausam mast mahiinaa (Ujala, 1959): In this Lata-Manna duet composed by Shankar-Jakishan, Lata nails a G5 (taar komal ga in the key of E) when she repeats the “yalla yalla” line in the taar saptak (high octave) at the end.

ajii ruuThkar ab kahaa.n jaayiega? (Aarzoo, 1965): Shankar-Jaikishan is once again the culprit here: listen as Lata reaches an Ab5 (taar shuddh ma in the key of Eb) in the antara of this gem picturized on Sadhana from Aarzoo. Regarding the high pitch of this song, Lata has said:

“I remember “ajii ruuThkar ab kahaa.n jaayiegaa” in Aarzoo (1965). What a high pitch that was! My ears reddened when I sang it. But I stubbornly sang at that impossible scale, refusing to admit defeat to any range. I would get very angry and sing at any range without complaining. Composers would take full advantage of my silence and keep raising the scale. In fact, I used to have arguments with Jaikishan. I would ask him, “kyaa baat hai, aap merii pariksha le rahe hai.n? mai.ne aap kaa kyaa bigaDaa hai jo aap meraa kaan laal kar rahe hai.n? (What’s the matter? Why are you testing me? What have I done that you should trouble me so much to redden my ears?)’

jiyaa o jiyaa kuch bol do (Jab Pyar Kisi Se Hota Hai, 1961): The tandem effect described below with “ahsaan teraa hogaa mujh par” is also observed here. Lata gives it her all as she reaches a Ab5 (taar komal ni in the key of Bb) in the antara of the female tandem version of the fun Rafi classic from Jab Pyar Kisi Se Hota Hai.

rasik balmaa (Chori Chori, 1957): This Raga Shuddh Kalyan-based Shankar-Jakishan composition is one of my all-time favorites! Lata hits a G#5 (taar shuddh ga in the key of E) when she sings the antara.

ahsaan teraa hogaa mujh par (Junglee, 1961): The Rafi version of this number is an all-time classic. Although the Lata version is less popular, it is still beautiful in its own right and brings up an interesting point about scales in tandem songs from this era. In almost all cases that I can think of, music directors made the female singer of a tandem song sing her versions in the same key as the male verion. Because men tend to be more comfortable in the higher register of their voices than women, this practice often put the female playback singer at a disadvantage when it came to hitting the highest notes of the composition. But who else would be up for the challenge of adjusting to the “male scale,” if not Lata Mangeshkar? She hits a G#5 (taar shuddh ga in the key of E) in the antara of this evergreen Shankar-Jakishan composition based in raga Yaman. Regarding the difficulties of singing tandem songs, Lata has remarked:

Actually, “ahsaan teraa hogaa mujh par” was only meant to be sung by Rafi. But the film’s hero, Shammi Kapoor, suddenly decided that the heroine should sing it as well. It was picturised with Rafi’s voice on Saira Banu and later dubbed by me. So I had to sing it in the same sur as Rafi. The same was done with “jiyaa o jiyaa kuch bol do.“

tere baadalo.n kii khair (Champakali, 1957): This Bhairavi-based composition composed by Hemant Kumar and picturized on Suchitra Sen is not as well-known as the rest of the songs on this list, but it’s worth mentioning for the A5 (taar ma in the key of E) that Lata hits at its conclusion.

ahaa rimjhim ke yeh pyaare pyaare geet (Usne Kaha Tha, 1960): Salil Chowdhury was known for his incorporation of ideas of Western classical music into his Indian compositions. As an example, he has Lata sing an operatic-style counterpoint passage here in which she reaches an Bb5 (ati–taar sa in the key of Bb) against Talat’s rendering of the mukhda at the end of this composition. Subtle, but exquisite!

aa ab laut chale.n (Jis Des Mein Ganga Behti Hai, 1960): Shankar-Jaikishan score another point here with this patriotic composition from Jis Des Mein Ganga Behti Hai. Mukesh and Lata both sing this song, but it is not structured as a prototypical romantic duet. Mukesh takes the main lines while Lata provides a few supporting lines and interesting background vocals, including the virtuosic glide in which she nails an Bb5 (taar pa in the key of Eb) with finesse.

aaja bha.nvar/jhananana jhan baaje paayalia (Rani Roopmati, 1957): Both of these drut bandishes based in Raga Brindavani Sarang and composed by S.N. Tripathi from Rani Roopmati are truly virtuosic by Bollywood standards. Lata sounds so impressive when she nails the Bb5 (taar pa in the key of Bb) at the end of both “aaja bha.nvar” and “jhananana jhan.” In addition to showing off her range, Lata also showcases her classical training and vocal dexterity as she navigates through a host of intricate taans in both songs. I have to say Lata’s virtuosity leaves Rafi in the dust in the duet here (sorry, Mrs. 55!).

ham ramchandra kii chandrakala me.n bhii (Sampoorna Ramayana, 1961): The Mangeshkar sisters team up here to sing a duet from Sampoorna Ramayana composed by Vasant Desai. It’s somewhat interesting to note that the song here is actually picturized on two pre-pubescent boys, who are receiving playback from female singers. At the end of the song, there is a dramatic ascent in the melody until both sisters climax at a powerful Bb5 (taar pa in the key of Eb).

ai dil kahaa.n terii manzil (Maya, 1961): Salil Chowdhury makes another contribution to our list with this composition rendered by Dwijen Mukherjee (a noted Bengali singer with a voice similar to Hemant Kumar’s) and Lata. Like “aa ab laut chale.n,” this duet is not structured traditionally; rather, Dwijen sings the main lines and Lata provides background support. Lata sounds heavenly as she hits a Bb5 (taar shuddh dha in the key of Db) in one of Salil’s signature opera-inspired vocal passages.

woh ek nigaah kyaa milii (Half-Ticket, 1962): To the best of my knowledge, Salil Chowdhury wins the contest for having recorded Lata’s voice at its highest pitch in the history of Bollywood cinema with this composition. In this duet with Kishore Kumar picturized on Helen, Lata manages to hit the elusive soprano C6 (taar shuddh dha in the key of Eb) in the second staccato sequence of the interlude played between stanzas. Her voice is so high here that it blends in naturally with the instrumental piccolo parts. Nailing a staccato passage in the soprano register like this is incredibly impressive for a vocalist trained in the Indian tradition (in which the emphasis is not placed on vocalizing at the extremes of one’s range)–brava, Lata, brava!

Asha Bhonsle: Selected High Notes

sakhii rii sun bole papiihaa us paar (Miss Mary, 1957): You get the opportunity to hear some some sibling rivalry in this Hemant Kumar composition loosely based on Raga Tilang from Miss Mary! Lata (on Meena Kumari) and Asha (on some rando actress I can’t recognize) duke it out at the end with some intricate taans, but Asha actually takes the more complex passages and touches an Ab5 (taar shuddh ma in the key of Eb)in her last taan here. For those keeping score, Lata also hits the same note in her taan right before.

dil na kahii.n lagaanaa (Ghunghat, 1960): I hadn’t heard this Ravi composition picturized on Helen before doing research for this post, but it’s quite special. The song is divided into several differents segments with lyrics in four different languages: Hindi, Tamil, Bengali (a cover of Geeta Dutt’s classic “tumi je amar“), and Punjabi. During in an alaap in the final Punjabi segment, Asha manages to hit an A5 (taar shuudh re in the key of G).

tarun aahe ratra ajunii (Non-Film): This composition by Hridaynath Mangeshkar is a Marathi bhavgeet, so I guess it technically doesn’t belong on the list. Even though I don’t understand the Marathi lyrics, this is one of my favorite Asha songs because the tune and rendition are simply sublime. Here, the line “bagh tula pusatos aahe” begins on Bb3 and climbs up to A5 (taar shuddh ni in the key of Bb) with the ornament Asha sings on the words “gaar vaaraa.” In the span of one musical line, Asha covers nearly two octaves of vocal range–wow!

suunii suunii saa.ns kii sitaar par (Lal Patthar, 1971): This Shankar-Jakishan composition picturized on Rakhee from Lal Patthar is a beautiful example of the use of Raga Jayjayvanti in filmi music. In a passage towards the end of the song (beginning at 3:13), Asha touches a Bb5 (taar komal ga in the key of G). She also finishes the song off with some powerful taans. For comparison, see Shankar-Jakishan’s Jayjayvanti beauty from Seema sung by Lata (note the exquisite taankari at the end!): manmohana baDe jhuuThe.

daiyaa mai.n kahaa.n aa pha.nsii (Caravan, 1971): This song from Caravan is probably remembered more for Asha Parekh’s crazy dance moves than its musical underpinnings, but this song is composed in a manner that is rather unique for Bollywood music. Most songs in Bollywood are sung at a fixed tonic (sa), but R.D. Burman experiments with a musical technique all too familiar to those who listen to 90s Western pop: the key change. He goes wild here by changing the tonic of the song by half-steps multiple times, and Asha hits a Bb5 during a transition at the very end.

Asha Parekh hides herself on stage during the performance of “daiyaa mai.n kahaa.na aa pha.nsii” in Caravan (1971)

aa dekhe.n zaraa (Rocky, 1981): Despite my aversion to Bollywood music from the 80s, I still decided to include this song on the list for the Bb5 (taar pa in the key of Eb) that Asha manages to yell out at around 2:20.

nadii naa re na jaao shyaam (Mujhe Jeene Do, 1963): In the alaap of this Jaidev composition picturized on Waheeda Rahman, Asha nails a G#5 and briefly touches a B5 (taar pa in the key of E) before descending to pitches that are more comfortable for the average mortal.

tu mi piaci cara (Bewaqoof, 1960): This cute S.D. Burman composition sung by Asha and Kishore features an opening line in Italian. Maybe it was the Italian lyrics that inspired S.D. Burman to have Asha sing some background operatic passages in addition to her normal lines. During one of these passages before the second-last antara, Asha hits a B5 (taar ma in the key of F#).

jo mai.n hotaa ek TuuTaa taaraa (Chhupa Rustam, 1973): This composition by S.D. Burman rendered by Asha and Kishore features some more opera-like passages at its conclusion. Asha is impressively comfortable as she nails a B5 (ati-taar sa in the key of B) several times in a row as counterpoint against Kishore’s rendering of the mukhda!

o merii jaa.n maine kahaa (The Train, 1970): You wouldn’t expect this fun item number composed by R.D. Burman and picturized on Helen from The Train to be particularly virtuosic in terms of vocals, but Asha actually hits the a B5 (ati-taar sa in the key of B) in the song’s opening line with her leap on the word “kahaa.” For those of you listening very carefully, it’s important to keep in mind that the film version appears to be transposed a half-step higher than the album version of this song.

If you’ve managed to pay attention so far and take a listen to some of these songs, you may have noticed some interesting trends when comparing the high notes rendered by our two beloved Bollywood divas. After taking a look at the years I’ve listed next to each song, you’ll notice that all of Lata’s highest notes on this list span a range of nine years from 1956 to 1965, while Asha’s highest notes range over 24 years (!) from 1957 to 1981. The broad range of years in which Asha hit her high notes might provide evidence to those who support the notion that Asha’s voice aged better than Lata’s over the decades. But there is one caveat: the manner in which these two divas produce their high notes is distinct and may play a role in mediating this trend. If you listen carefully, you can hear that Lata always employs her “chest voice” to belt out the notes of a composition, even at the highest registers. On the other hand, Asha often employs her “head voice,” the more commonly used technique by female singers to access high notes. Head voice has a softer, gentler sound because it resonates around the nasal cavity instead of the chest during vocal production. This technique of singing is traditionally forbidden in the Indian classical tradition, so purists might consider some of Asha’s highest highs as “cheating”–head voice is sometimes even referred to as naqlii avaaz (fake voice). I’m not so much of a purist that I would discredit Asha for using her head voice in these compositions, but I will venture to say that, if asked to do so, she would not be able to hit the notes of the high soprano register in her later years using her chest voice as gracefully as Lata did during her peak.

Another interesting trend to note is how different music directors composed differently to suit the individual styles of Lata or Asha. Although all the music directors on this list have worked extensively with both sisters, the music directors who asked Lata to sing at her highest range are not the same as the music directors who asked the same of Asha. Shankar-Jaikishan and Salil Chowdhury, by far, contribute to Lata’s highest record pitches whereas R.D. Burman and S.D. Burman seem to have saved their highest notes for Asha. Just some food for thought.

R.D. Burman teaches Asha Bhonle during a rehearsal session.

Please let us know if you find any more examples of Lata and Asha’s highest highs that are not on this list! I have attempted to find the best examples, but given the vast repertoire of Bollywood film music, I may have naturally missed out on some that are worth mentioning. Also, if you enjoyed this post, let us know in the comments and I’ll try to do some similar-themed posts in the future–perhaps next, we can take a listen to Lata and Asha’s lowest recorded notes or a an analysis of the Bollywood tenor’s highest highs? The possibilities are endless!

-Mr. 55