I feel like we’ve all been in this situation at some point: one of your favorite aunties steps up to the microphone at the annual Diwali function, and you have a sinking fear in your heart that she’s going to embarass herself by butchering another Lata classsic on stage. As she struggles through the sky-high notes of the antara, you cringe and ask yourself why you’re here again, subjecting yourself to this torture…

Well, it turns out it’s not entirely her fault. The reality of the situation is that Bollywood songs from the Golden Era tend to be pitched at extremely high scales for the average female singer. Unless a woman is a veritable soprano like Lata Mangeshkar or Asha Bhonsle, it is going to be quite a challenge for them to sing many of the classic songs from this period in their original keys. The high-pitched soprano female voice has become a hallmark of Hindi film music, and I’d like to explore this phenomenon in greater detail with this post.

Two sisters who changed playback singing forever: Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhonsle.

Why are Bollywood songs for females from the Golden Era pitched at astronomically high scales? I don’t know for sure, but I definitely have a few ideas that could explain this trend. First, the high-pitched female voice is consistent with the image of the ideal Indian woman that was prevalent during the 1950s and 60s. The soprano register suggests innocence and purity, which enhanced the traditionally feminine perceptions of heroines advanced by film directors of the time. Lata Mangeshkar is the ultimate example of this phenomenon; her voice, with its ethereal purity, has been considered the traditional female voice of India for decades. However, this explanation is less pertinent to Lata’s younger sister Asha Bhonsle. The voice of Asha, who was widely known for her experimentation with non-traditional genres such as the cabaret, is not a national emblem of purity in the same way as her elder sister’s. For this reason, an alternative explanation is needed to describe the popularity of the soprano female voice in Bollywood, and I would venture to say that this alternative explanation is rooted in musical origins. Before the arrival of the Mangeshkars onto the filmi musical scene, female singing in Hindi films was dominated by artists with heavy, nasal voices, such as Suraiyya and Shamshad Begum. Once music directors had the opportunity to work with the Mangeshkars, things changed forever: the nasalized heavy female voices were out and the delicate soprano voices were here to stay. After Lata and Asha became established as playback singers, I would argue that music directors of the time pushed the boundaries of their compositions in terms of range to test and showcase the virtuosity of these two exceptional talents.

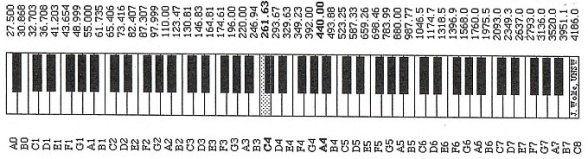

Before we take a listen to some of Lata and Asha’s highest highs throughout Bollywood’s musical history, explaining a little bit of musical nitty-gritty is necessary to fully appreciate the gist of what’s going on here. From my experiences with transcribing and performing many songs from this era, I would estimate that the vast majority (perhaps 90%?) of songs composed for Lata and Asha max out at F5 or F#5 (two F/F#’s above middle C on the piano) as their highest note. Therefore, in the brief list of high notes that I’ve compiled below, I’ve only chosen to include those rare songs that surpass the typical upper limit of F#5. Songs for both singers are listed in order of ascending pitch of the composition’s highest note.

Keyboard labeled with note names and frequencies. C4 is taken as middle C. The high notes listed here range from G5 to C6.

Lata Mangeshkar: Selected High Notes

jhuumta mausam mast mahiinaa (Ujala, 1959): In this Lata-Manna duet composed by Shankar-Jakishan, Lata nails a G5 (taar komal ga in the key of E) when she repeats the “yalla yalla” line in the taar saptak (high octave) at the end.

ajii ruuThkar ab kahaa.n jaayiega? (Aarzoo, 1965): Shankar-Jaikishan is once again the culprit here: listen as Lata reaches an Ab5 (taar shuddh ma in the key of Eb) in the antara of this gem picturized on Sadhana from Aarzoo. Regarding the high pitch of this song, Lata has said:

“I remember “ajii ruuThkar ab kahaa.n jaayiegaa” in Aarzoo (1965). What a high pitch that was! My ears reddened when I sang it. But I stubbornly sang at that impossible scale, refusing to admit defeat to any range. I would get very angry and sing at any range without complaining. Composers would take full advantage of my silence and keep raising the scale. In fact, I used to have arguments with Jaikishan. I would ask him, “kyaa baat hai, aap merii pariksha le rahe hai.n? mai.ne aap kaa kyaa bigaDaa hai jo aap meraa kaan laal kar rahe hai.n? (What’s the matter? Why are you testing me? What have I done that you should trouble me so much to redden my ears?)’

jiyaa o jiyaa kuch bol do (Jab Pyar Kisi Se Hota Hai, 1961): The tandem effect described below with “ahsaan teraa hogaa mujh par” is also observed here. Lata gives it her all as she reaches a Ab5 (taar komal ni in the key of Bb) in the antara of the female tandem version of the fun Rafi classic from Jab Pyar Kisi Se Hota Hai.

rasik balmaa (Chori Chori, 1957): This Raga Shuddh Kalyan-based Shankar-Jakishan composition is one of my all-time favorites! Lata hits a G#5 (taar shuddh ga in the key of E) when she sings the antara.

ahsaan teraa hogaa mujh par (Junglee, 1961): The Rafi version of this number is an all-time classic. Although the Lata version is less popular, it is still beautiful in its own right and brings up an interesting point about scales in tandem songs from this era. In almost all cases that I can think of, music directors made the female singer of a tandem song sing her versions in the same key as the male verion. Because men tend to be more comfortable in the higher register of their voices than women, this practice often put the female playback singer at a disadvantage when it came to hitting the highest notes of the composition. But who else would be up for the challenge of adjusting to the “male scale,” if not Lata Mangeshkar? She hits a G#5 (taar shuddh ga in the key of E) in the antara of this evergreen Shankar-Jakishan composition based in raga Yaman. Regarding the difficulties of singing tandem songs, Lata has remarked:

Actually, “ahsaan teraa hogaa mujh par” was only meant to be sung by Rafi. But the film’s hero, Shammi Kapoor, suddenly decided that the heroine should sing it as well. It was picturised with Rafi’s voice on Saira Banu and later dubbed by me. So I had to sing it in the same sur as Rafi. The same was done with “jiyaa o jiyaa kuch bol do.“

tere baadalo.n kii khair (Champakali, 1957): This Bhairavi-based composition composed by Hemant Kumar and picturized on Suchitra Sen is not as well-known as the rest of the songs on this list, but it’s worth mentioning for the A5 (taar ma in the key of E) that Lata hits at its conclusion.

ahaa rimjhim ke yeh pyaare pyaare geet (Usne Kaha Tha, 1960): Salil Chowdhury was known for his incorporation of ideas of Western classical music into his Indian compositions. As an example, he has Lata sing an operatic-style counterpoint passage here in which she reaches an Bb5 (ati–taar sa in the key of Bb) against Talat’s rendering of the mukhda at the end of this composition. Subtle, but exquisite!

aa ab laut chale.n (Jis Des Mein Ganga Behti Hai, 1960): Shankar-Jaikishan score another point here with this patriotic composition from Jis Des Mein Ganga Behti Hai. Mukesh and Lata both sing this song, but it is not structured as a prototypical romantic duet. Mukesh takes the main lines while Lata provides a few supporting lines and interesting background vocals, including the virtuosic glide in which she nails an Bb5 (taar pa in the key of Eb) with finesse.

aaja bha.nvar/jhananana jhan baaje paayalia (Rani Roopmati, 1957): Both of these drut bandishes based in Raga Brindavani Sarang and composed by S.N. Tripathi from Rani Roopmati are truly virtuosic by Bollywood standards. Lata sounds so impressive when she nails the Bb5 (taar pa in the key of Bb) at the end of both “aaja bha.nvar” and “jhananana jhan.” In addition to showing off her range, Lata also showcases her classical training and vocal dexterity as she navigates through a host of intricate taans in both songs. I have to say Lata’s virtuosity leaves Rafi in the dust in the duet here (sorry, Mrs. 55!).

ham ramchandra kii chandrakala me.n bhii (Sampoorna Ramayana, 1961): The Mangeshkar sisters team up here to sing a duet from Sampoorna Ramayana composed by Vasant Desai. It’s somewhat interesting to note that the song here is actually picturized on two pre-pubescent boys, who are receiving playback from female singers. At the end of the song, there is a dramatic ascent in the melody until both sisters climax at a powerful Bb5 (taar pa in the key of Eb).

ai dil kahaa.n terii manzil (Maya, 1961): Salil Chowdhury makes another contribution to our list with this composition rendered by Dwijen Mukherjee (a noted Bengali singer with a voice similar to Hemant Kumar’s) and Lata. Like “aa ab laut chale.n,” this duet is not structured traditionally; rather, Dwijen sings the main lines and Lata provides background support. Lata sounds heavenly as she hits a Bb5 (taar shuddh dha in the key of Db) in one of Salil’s signature opera-inspired vocal passages.

woh ek nigaah kyaa milii (Half-Ticket, 1962): To the best of my knowledge, Salil Chowdhury wins the contest for having recorded Lata’s voice at its highest pitch in the history of Bollywood cinema with this composition. In this duet with Kishore Kumar picturized on Helen, Lata manages to hit the elusive soprano C6 (taar shuddh dha in the key of Eb) in the second staccato sequence of the interlude played between stanzas. Her voice is so high here that it blends in naturally with the instrumental piccolo parts. Nailing a staccato passage in the soprano register like this is incredibly impressive for a vocalist trained in the Indian tradition (in which the emphasis is not placed on vocalizing at the extremes of one’s range)–brava, Lata, brava!

Asha Bhonsle: Selected High Notes

sakhii rii sun bole papiihaa us paar (Miss Mary, 1957): You get the opportunity to hear some some sibling rivalry in this Hemant Kumar composition loosely based on Raga Tilang from Miss Mary! Lata (on Meena Kumari) and Asha (on some rando actress I can’t recognize) duke it out at the end with some intricate taans, but Asha actually takes the more complex passages and touches an Ab5 (taar shuddh ma in the key of Eb)in her last taan here. For those keeping score, Lata also hits the same note in her taan right before.

dil na kahii.n lagaanaa (Ghunghat, 1960): I hadn’t heard this Ravi composition picturized on Helen before doing research for this post, but it’s quite special. The song is divided into several differents segments with lyrics in four different languages: Hindi, Tamil, Bengali (a cover of Geeta Dutt’s classic “tumi je amar“), and Punjabi. During in an alaap in the final Punjabi segment, Asha manages to hit an A5 (taar shuudh re in the key of G).

tarun aahe ratra ajunii (Non-Film): This composition by Hridaynath Mangeshkar is a Marathi bhavgeet, so I guess it technically doesn’t belong on the list. Even though I don’t understand the Marathi lyrics, this is one of my favorite Asha songs because the tune and rendition are simply sublime. Here, the line “bagh tula pusatos aahe” begins on Bb3 and climbs up to A5 (taar shuddh ni in the key of Bb) with the ornament Asha sings on the words “gaar vaaraa.” In the span of one musical line, Asha covers nearly two octaves of vocal range–wow!

suunii suunii saa.ns kii sitaar par (Lal Patthar, 1971): This Shankar-Jakishan composition picturized on Rakhee from Lal Patthar is a beautiful example of the use of Raga Jayjayvanti in filmi music. In a passage towards the end of the song (beginning at 3:13), Asha touches a Bb5 (taar komal ga in the key of G). She also finishes the song off with some powerful taans. For comparison, see Shankar-Jakishan’s Jayjayvanti beauty from Seema sung by Lata (note the exquisite taankari at the end!): manmohana baDe jhuuThe.

daiyaa mai.n kahaa.n aa pha.nsii (Caravan, 1971): This song from Caravan is probably remembered more for Asha Parekh’s crazy dance moves than its musical underpinnings, but this song is composed in a manner that is rather unique for Bollywood music. Most songs in Bollywood are sung at a fixed tonic (sa), but R.D. Burman experiments with a musical technique all too familiar to those who listen to 90s Western pop: the key change. He goes wild here by changing the tonic of the song by half-steps multiple times, and Asha hits a Bb5 during a transition at the very end.

Asha Parekh hides herself on stage during the performance of “daiyaa mai.n kahaa.na aa pha.nsii” in Caravan (1971)

aa dekhe.n zaraa (Rocky, 1981): Despite my aversion to Bollywood music from the 80s, I still decided to include this song on the list for the Bb5 (taar pa in the key of Eb) that Asha manages to yell out at around 2:20.

nadii naa re na jaao shyaam (Mujhe Jeene Do, 1963): In the alaap of this Jaidev composition picturized on Waheeda Rahman, Asha nails a G#5 and briefly touches a B5 (taar pa in the key of E) before descending to pitches that are more comfortable for the average mortal.

tu mi piaci cara (Bewaqoof, 1960): This cute S.D. Burman composition sung by Asha and Kishore features an opening line in Italian. Maybe it was the Italian lyrics that inspired S.D. Burman to have Asha sing some background operatic passages in addition to her normal lines. During one of these passages before the second-last antara, Asha hits a B5 (taar ma in the key of F#).

jo mai.n hotaa ek TuuTaa taaraa (Chhupa Rustam, 1973): This composition by S.D. Burman rendered by Asha and Kishore features some more opera-like passages at its conclusion. Asha is impressively comfortable as she nails a B5 (ati-taar sa in the key of B) several times in a row as counterpoint against Kishore’s rendering of the mukhda!

o merii jaa.n maine kahaa (The Train, 1970): You wouldn’t expect this fun item number composed by R.D. Burman and picturized on Helen from The Train to be particularly virtuosic in terms of vocals, but Asha actually hits the a B5 (ati-taar sa in the key of B) in the song’s opening line with her leap on the word “kahaa.” For those of you listening very carefully, it’s important to keep in mind that the film version appears to be transposed a half-step higher than the album version of this song.

If you’ve managed to pay attention so far and take a listen to some of these songs, you may have noticed some interesting trends when comparing the high notes rendered by our two beloved Bollywood divas. After taking a look at the years I’ve listed next to each song, you’ll notice that all of Lata’s highest notes on this list span a range of nine years from 1956 to 1965, while Asha’s highest notes range over 24 years (!) from 1957 to 1981. The broad range of years in which Asha hit her high notes might provide evidence to those who support the notion that Asha’s voice aged better than Lata’s over the decades. But there is one caveat: the manner in which these two divas produce their high notes is distinct and may play a role in mediating this trend. If you listen carefully, you can hear that Lata always employs her “chest voice” to belt out the notes of a composition, even at the highest registers. On the other hand, Asha often employs her “head voice,” the more commonly used technique by female singers to access high notes. Head voice has a softer, gentler sound because it resonates around the nasal cavity instead of the chest during vocal production. This technique of singing is traditionally forbidden in the Indian classical tradition, so purists might consider some of Asha’s highest highs as “cheating”–head voice is sometimes even referred to as naqlii avaaz (fake voice). I’m not so much of a purist that I would discredit Asha for using her head voice in these compositions, but I will venture to say that, if asked to do so, she would not be able to hit the notes of the high soprano register in her later years using her chest voice as gracefully as Lata did during her peak.

Another interesting trend to note is how different music directors composed differently to suit the individual styles of Lata or Asha. Although all the music directors on this list have worked extensively with both sisters, the music directors who asked Lata to sing at her highest range are not the same as the music directors who asked the same of Asha. Shankar-Jaikishan and Salil Chowdhury, by far, contribute to Lata’s highest record pitches whereas R.D. Burman and S.D. Burman seem to have saved their highest notes for Asha. Just some food for thought.

R.D. Burman teaches Asha Bhonle during a rehearsal session.

Please let us know if you find any more examples of Lata and Asha’s highest highs that are not on this list! I have attempted to find the best examples, but given the vast repertoire of Bollywood film music, I may have naturally missed out on some that are worth mentioning. Also, if you enjoyed this post, let us know in the comments and I’ll try to do some similar-themed posts in the future–perhaps next, we can take a listen to Lata and Asha’s lowest recorded notes or a an analysis of the Bollywood tenor’s highest highs? The possibilities are endless!

-Mr. 55

I think that the sisters and their high pitched voices over such a long time dominating Indian cinema has had a huge influence in the way Indian woman perceive themselves and are perceived. They have long been child like-women who need to be taken care of and timid, in support roles rather than in equal or powerful positions. It is only recently that cinema is breaking many old taboos and I think the sisters voices have also changed and deepend allowing a stronger womanly role to come out.

Ah yes, an interesting point!

In recent years, Bollywood cinema has witnessed the rise of a deeper alto voice that is more appropriate for seductive songs and item numbers (e.g. Sunidhi Chauhan in “sheila ki javaanii”). So, while current Bollywood has modernized the image of the Indian woman by allowing heroines to be more sexually liberated in appearance and behavior, it is debatable whether this modernization is sending a positive message or leading to the further objectification of women. This discussion begs the question: is today’s image of the Bollywood heroine a step forward from the virtuous and pure ideal of femininity established by female characters in the Golden Era (and further shaped by the voices of Lata and Asha)?

lol…that is a very interesting and probably politicaly incorrect question. In our contemporary climate it would probably meet with quite a hostile response. I think that modesty and purity are very attractive traits in both men and women. Perhaps it is the double standard applied to men and women even now, that make some women reluctant to attribute much importance to them. I guess one of the premises underlying the sexual revolution for feminists was ‘if men can do it why can’t we’….it was one of the contributing factors underlying their instrumental role in that social movement, but it’s still a very shaky and spurious motivation in itself. Another was that all these idea’s of modesty and institutions such as marraige are mere social constructs and oppressive ones at that. I think that, in some respects, today’s image of the Bollywood heroine is definately a step backwards.

That said, there was something disempowering in the utterly self-effacing wife portrayed in the Indian cinema of yesteryears, a woman who had no notion of personhood independent of her status as wife or mother. It seems a little mean, but there is something slightly ludicrous about the sacrificing and utterly abject wife, portrayed in some 50’s movies such as Gharana or Dulhan. (I only saw these movies because I was besotted with Raaj Kumar post Pakeezah). Not to say self sacrifice isn’t noble but responding in that way to a husbands crushing, disdainful and completely selfish behaviour, somehow lacks in integrity. It usually didn’t help the woman herself or help her husband see his wrong. I guess sometimes assertive behaviour is what the occasion requires. More fundamentally these movies didn’t seem to realise that women are thinking, sentient, reflective beings not just to be crushed and trampled over scott free, even if the husband ultimately came home repentant.

sirji,listen the full song tere khayalo me hum -geet gaaya pathharone for ashajis peak and resonance with flute in second time sung lines not found on records.

Thanks for your insightful comments!

As you have said, modesty is a value that is held up as a double standard in Bollywood cinema, and this double standard has led to the oppression of Indian women for decades. The extreme importance placed on modesty for women and not men has led to the creation of female roles with little autonomy whose worth is defined by their relationships to other men. I can only think of a handful of strong, independent female characters from the Golden Era (and even these aren’t perfect examples): Nargis in Mother India (1957), Waheeda Rehman in Guide (1965), and Smita Patil in Bhumika (1977).

Pingback: Which Actor Did Hemant Kumar Sing For Best? « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

Pingback: Kuch Dil Ne Kaha Lyrics and Translation: Let’s Learn Urdu-Hindi « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

Dear Mr/Mrs 55,

This is a wonderful blog….and I really enjoyed this particular post. I am somewhat surprised that Lataji actually hit a high C. She appeared uncomfortable in the high notes of Ehsaan Tera Hoga and Aji Roothkar which (as you wrote) are much lower than the high C. I look forward to checking this out tonight! Sometime back I had transcribed O Duniya Ke Rakhwale—which I had until recently thought of as the song with the highest non-falsetto notes. Depending on which version you transcribe from YouTube, Rafiji hits Bb or B in that song. I was surprised to find that recently there is indeed a Bollywood male singer who manged to (without using falsetto) touch high C: Rahat Fateh Ali Khan. In the song, Tujhe Dekh Dekh Sona, he does so in the phrase in quotes: kab se hai dil mein mere, armaan “kayi” unkahe.

Since Mrs 55 is a fan of Rafiji (like I), I hope you all write an article on him also…

Cheers, Pradeep

Hi Pradeep! It is quite interesting to note the variability from song to song in the comfort that Lata displayed at higher registers. She could soar to hit the very high notes without strain in some songs (e.g. woh ek nigaah kyaa milii) but then sound strained hitting notes at lower pitches (e.g. dil teraa diivaanaa hai sanam). I would guess that this had something to do with the condition and health of her voice at the time of recording.

Rafi was a veritable tenor and has indeed hit some stellar high notes, as you’ve noted, for example, in “o duniyaa ke rakhvaale.” Rahat Fateh Ali Khan and his uncle Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan can hit very high notes without falsetto, but to my ears, their voices lack the pleasant finesse found in the tenors of classic Bollywood. We will hopefully do a sequel to this post to discuss high male notes in Hindi film music in the coming weeks! Stay tuned.

Your comment about the variability in Latiji’s ease in hitting the high notes is interesting. I will pay more attention to this as I spend the weekend browsing the songs you have compiled—with my piano in close proximity (:-)

You are right about issues of finesse at those stratospheric notes. Most singers, at that point, just focus on pitching those notes correctly and usually expression and beauty takes a backstage. Rafiji, which is why I cannot get enough of him, was an exception. I look forward to your sequel post!

Regards, Pradeep

I believe that the basic difference in the pitch and structure of the male and female voices makes direct comparisons seem unauthentic. For example when you are talking about the high C Lata has hit, it is C6, and the one Rahat has hit is actually C5 (one octave lower). Thats simply because a male tenor voice is still below a female soprano voice. So the two C’s we are comparing are very different really. Ditto while comparing Lata and Rafi.

Yes, of course, but comparisons between the ranges of a male and a female are generally made by shifting the female octave by 1.

It is much easier , in general, for a male to hit a G4 (and it is quite common too) than it is for a woman to hit G5 (this is uncommon). The reverse is probably true at low ranges ; females hit notes like D3 with relative ease ; D2 for a male is much harder, I think.

What a great write up! We seem to think exactly alike in many respects 😀

Having said that, here is my two bits: It is not correct to say that the songs you selected for Lata are between 1957-62. Chori Chori (Rasik Balma) was 1956 and Arzoo (Aji rooth kar ab) was 1965.

And did you miss out Lata’s famous Meera Bhajans of 1968 (1969?) I think that in the antaras of “Mhara ri Giridhar Gopal” , she does go very high although I’m not sure what the notes are.

All said and done, it was sheer pleasure to have chanced upon your brilliantly researched and written piece sir! God bless!

Thanks for reading! Good catch about the years–even still, Lata’s highest notes span a significantly narrower range of time than Asha’s.

In “mhaaraa re” from Lata’s Meera bhajan album (1968) for her brother Hridaynath, Lata soars to an Ab5 (taar paa in the key of Db) in the antara.

Pingback: Page not found « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

Pingback: Ehsaan Tera Hoga Mujhpar Lyrics and Translation: Let’s Learn Urdu-Hindi « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

Pingback: Raat Akeli Hai Lyrics and Translation: Let’s Learn Urdu-Hindi « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

for lata I think there is even do dil toote do dil haare from Heer Ranjha & haye re woh din kyon na aaye from Anuradha

also in later years you may find Yaara sili sili from lekin and Dil hoom hoom kare from Rudaali

Awesome post, exhaustive research. What about singers like Kavita Krishnamurthy or Chitra or even Shreya Goshal? Do you know anything about the notes – highs they tried? Just as a way to compare the new singers with the two divas. I am finding all of these new reality show winners using the deeper alto voice that Sunidhi Chauhan used. I miss the purist tone of the Golden years and sometimes wish for Lataji to sing a new song again.

Excelent article. There are many gems in Marathi where this duo has done amazing work. Like Chaand Kevadyachi Raat by Lata and Jeevalaga by Asha.

One minor correction. Nirupama Roy was the lead actress in Rani Rupamati and not Nimmi.

(first time commentor) I don’t understand the technicalities of music, but I enjoyed this post! As was reading this, the ‘Tu hi re’ song from Bombay [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FH7OXblvPg8] was on in my media player. Kavita Krishnamurthy [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kavita_Krishnamurthy] hits some pretty high notes there too. Thought it would be interesting to see something similar on her. Pretty please?

though C6 is the defining note of a soprano.

Came across this post when I was reading up on tandem songs in Hindi films. very glad to stumble across such a great blog. Have added you to my feedly and look forward to many more posts.

I had always thought that it was unfair to Lata to be asked to sing the solos sung by male singers first. The pitch became very high and as she could handle it, the music directors didnt tax themselves too much to adjust the pitch of the accompanying score. Lata made it easier for them, I think!

Excellent article except that it is wrong to blame everything on the social psyche .I think blaming the two sisters for dominating the industry to the point of downsizing others is in order.I think Geeta Dutt was the voice of a common woman. and Indian women for an age forgot to sing in their original voice. Whereas classical ,semi classical.folk.western classical standardized.the other kind of voice.

Superb article! I see Rafiji came down bit for 2nd higher note unlike Didi in “aji roothkar” male version.

Sandeep

Pingback: Na Tum Humen Jano Lyrics and Translation: Let’s Learn Urdu-Hindi | Mr. & Mrs. 55 - Classic Bollywood Revisited!

Is there a follow up post? Thanks.

Pingback: Minoo Purushottam: Appreciation from a Former Student | Mr. & Mrs. 55 - Classic Bollywood Revisited!

excellent article. nice analysis.

May be the high pitch capability of Lata and Asha was initially found convinient to accompany male singers in duet, which male singers could sing in their original pitches instead of having to lower their pitch to suit the female voice ? I hear Lata got used to singing that pitch since she sang along with her father from childhood. And Asha perhaps followed her sister. That Lata sang those high notes in chest voice rather than in head-voice like Asha is a good observation. Or is it possible that Lata sang entirely in head voice while Asha sang chest in lower notes and then transitioned to head for higher notes ? Listening to the speaking voices of Lata and Asha, Lata speaks at a higher pitch (in head-voice ?) while Asha speaks in lower pitch (chest voice) hence this guess.

Excellent work ! I would like you to consider these songs as well :

Yeh Zindagi Usiki Hai (Anarkali, 1953) : At the Alvida stage (especially the last one).

Main Piya Teri (Basant Bahar, 1956) : The antaras.

Allah Tero Naam (Hum Dono, 1961): The antaras.

Rangeela Re (Prem Pujari,1970) : Both the opening and closing notes.

Mere Naina Saawan Bhadon (Mehbooba, 1976) : The antaras.

Mitwa (Shaan, 1980) : The opening notes.

Atal Chhatra Sachcha Darbar (Bhajan album,1985):The point where she sings Jeeveshwari, Jagdeeshwari, Sarveshwari.

Bheje Kahaar Piyaji Bulalo (Maachis, 1996) : The antaras.

Oopar Khuda (Kachche Dhaage, 1999) : The opening notes.

Maati Re Maati Re (God Mother, 1999)

Andhe Khawabon Ko (Saadgi, 2007)

Haaye Jiya roye is another one of Lata ji’s songs in which she hits really high notes.

Hi,

Really interesting article. Have been long thinking to update my knowledge about high notes sung by Lata ji and your article helped a lot.

Though I don’t know the technicalities of music but would like to know your opinion on two songs from the movie “ek duje ke liye” — “solah baras ki bali umar ko salam” and “tere mere beech mein”.

Thanks.

i have one song. i have checked that high note in this song. i think it is C6 .but you check whether it is C6 or not.

the song is chham se tera aana ho from 1952 film shin shinaki boobla boo .the note is in between the two antaras.

I must say it’s quite a good find. Kudos to you!

The issue is, both in Woh Ik Nigah Kya Mili and this one and like many operatic examples cited, the singers are using their False voice (Falsetto), not exactly with Head voice, which has mixed usage of Head & Chest. Almost everyone, with proper technique can hit a C6 with the Falsetto register.

You might want to check out what Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan belted at a live concert of Signal to Noise from Dead Man Walking!

Thnks!

Hi mrs 55! A very good list this, that you have compiled. There’s a song ‘man mohana’ in Seema. Lata Didi has a very high pitched antara in it. And ‘Jhoote naina bole’ from Lekin for Asha Tai. Also, yaara seeli seeli from Lekin for Lata Ji. Although its a 91 film (you can’t many good songs in the 80s and 90s before saajan) but had very good music.

Mrs 55, can you please translate the super hit S.D.Burman song Ramgeela Re from ‘Prem Pujari’? It would be very nice as you always give some background info about the songs you translate and it is so nice.

Both sisters were a relief for music directors because both could sing comfortably in the male register. Historically madam noorjahan (GRHS) could, with some encouragement and lots of coaxing, sing in the traditional c# scale making duets easy for the male counterpart. With the mangeshkar sisters and their naturally high pitch, it was the greatest blessing for music directors to experiment, stretch and challenge duets to a point where it used to be more of a challenge for the male singers to keep up with the tightness, clarity and purity of notes that these sisters ( well, Lata more than Asha) could belt especially in the upper register. In all honesty, the sound quality of Lata both in the upper and lower range was always constant as opposed to Ashas. But both were equally good in their own styles.

This is a very good and informative article. I have always known (heard) of Lata’s ability to sing in high to very high registers (sometimes hitting the notes that Rafi Saheb would) but with my limited knowledge of music, I was never able to know about or compare note for note if she really touched the same notes as Rafi. After reading this article I know a lot more about he musical reach and abilities. Thanks for churning this write up. I was wondering if the song Taqdeer Ka Fasana (the 2nd stanza in particular) from the movie Sehra could also qualify to be on this list?

It would. The highest note in that song is a G# (taar Madhyam).

Please allow me to add one more to the list ‘Sab kuch luta ke hosh mein aaye to kya kiya’. The last couple of lines of the song ‘Aye maut jald aa aaram to mile’?!?

An excellent post. Would love to the same treatment for male voices!

Hi

Thanks its good to have informative articles.good research. the bhajan sung by lata ‘Allah tero naam’ which i absolutely adore i think has been sung at a very high note and if I am correct Lata ji in one of her interviews shared how she was insisted to sing on such a high note.As sweet as her voice is I do feel perhaps some songs could have been sung at a slighlty lower pitch to get the best out of Latas original voice.Naheed

awesome blog… but i disagree about use of head voice.. lataji when hitting C6 aa dil kaha teri manzil, uses head voice. her voice looses its weight and becomes shrill and pulled almost near whistle, though greatly executed, its not in chest voice.

Chanced upon this post when looking for substantive descriptions of the difference between Lata and Asha. I am not well versed in music theory, I had a musician (Western classical) friend read this. He is familiar with the sisters’ singing. He said that sopranos of Western classical music tend to use their head voice. He thought that the relatively shorter life of Lata’s voice might be due to her predominant use of her head voice for the high notes.

I grew up listening to Bollywood music of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. In my musically uneducated mind, Asha’s voice is more interesting and complex. Although Lata can go higher with her chest voice and Asha “cheats” with her head voice, Asha can go much lower than Lata. E.g., RD Burman’s compositions of Dum maro dum (“Hare Rama Hare Krishna”); Jaan-e-jaan dhoodta phir raha (“Jawani Diwani”).

To me, Lata is marvelous in:

– Baiyan na dharo and Maayi ri (“Dastak”/MadanMohan)

– Raina beeti Jaaye (“Amar Prem”/RD Burman)

– Khaayi hai re humne kasam (“Talash”/SD Burman)

– Jaise radha ne mala japi (“Tere Mere Sapne”/SD Burman)

There are some of my favorite Lata songs, however, in which her high notes get unpleasant for me:

– Kaanton se kheench ke yeh aanchal (“Guide”/SD Burman)

– Megha chaaye aadhi raat (“Sharmilee”/SD Burman) – particularly the verses

– Rangeela re (“Prem Pujari”/SD Burman)

– Ruke ruke se qadam (“Mausam”/Madan Mohan)

Re how well the sisters’ voices express sensuality, there is no doubt of course about Asha, given her many songs of seduction, composed by OP Nayyar, for instance. Lata’s Tu chanda main chandni (“Reshma aur Shera”/Jaidev) is a gorgeous rendition of sensual longing. Ang se ang lagaale (“Elaan”/Shankar Jaikishen) is another, though I do have trouble with her high notes in this one.

I hear similarities between Asha and Ella Fitzgerald but I can’t articulate them in precise musical terms. Perhaps this is an interesting thing for you to discuss here.

I love your blog. A small correction. The one in the picture of Rani Roopmati is Nirupa Roy and not Nimmi. Thanks.

Wonderful article but i dont see the mention of the mixed voice. I would like to see the research on how Lata’s vocal chotds are even able to stretch that far.

Thank for the wonderful analysis.I thoroughly enjoyed it. The ‘random’ actress who played Asha’s role in the movie Miss Mary is the popular Telugu heroin Jamuna, who subsequently acted as heroin in some Hindi movies, like Humrahi opposite Rajendra Kumar.

For Seeing the note variation see the just two lines sung by lata ji in star guild awards, high notes, low notes, subtle pitch

By far the best analysis of the classic era singers! also, the notes! I’m a male tenor myself but constantly working on my voice my range spans from E2 to G#7 ( E2-C#5 with chest register), (up to G6 with headvoice/falsetto and G#7 with the whistle register) . thank you.:)

If you are indeed one of the few who can sing in the whistle register, why must you remain Anonymous?

Please listen to Lata’s Aa jaane jaan..aa meharban from film Paapi (1977). You will be surprised to listen to the range of her vocals. Its just outstanding.

Omg. Bro it’s a movie of 1983. Lata ji was 54 yrs old that time

Listened to this song for first time. Indeed Lataji sounds excellent in this song, especially in high pitch. Thank you very much for this suggestion .

Ghar aaya mera pardesi song of lata ji is from the movie Awaara(1951). In that movie she touched higher note A at the start. And also she sung a song in a movie calle “Sada sulan” in our country (Sri lanka). That song is ”Sri lanka ma priyadara ja bhoomi’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6GqeSrKujwU . In that song she sang in a huge range and it’s highest note is ‘taar komala Dha’. And the other one in Movie Pakeezah 1972. In The song ‘Mausam hai aashiqna’ of that movie, she touched High A flat note( taar komala Dha). And in the song “Aa jaane jaan aa meherban” of movie Paapi 1983 she sang high G flat note

I don’t know your music well and i mentioned the notes as I know. I know only the sinhala music of our country. I don’t know the names of the notes whether true or false. Plz try to get an idea.

Thank you

Sada sulan film of our country is released on 1955. Lata ji had come to Sri lanka for the recordings. She had sung two songs of that movie. And those two are the only songs she had sung in Sinhala

An exceptionally well written article, and a pleasure to read. It is rare to find this kind of research into the technicalities of Indian playback singers.

Would you be doing a follow up for the male playback singers as well? Am interested in Rafi in particular. In my research have found several songs that touch (non falsetto, mixed/head) A#4 (na to karvaan ki talaash, ae mohabbat zindabaad, baat chalat nai chunari rang daari). Some of these are long, sustained holds at A#4. Would be very interested if there are any that go higher.

I don’t know if you will read this 9 years late, but I wanted to let you know how much I appreciate this very well-written blogpost. I’m a teenager and have just discovered the beauty of old Indian classics by Lataji and Ashaji. I sing myself and have a particularly low range for a girl, and I as confused whether or not it would be considered cheating if I sang these songs using my head voice. The way Asha Bhosle used her head voice is very interesting and I will listen to her songs more carefully now. I’ve always been more comfortable singing Kishore Da or Rafi Sahb’s songs and imitating their styles of singing than Lataji or Ashaji’s. I guess nowadays there is a wide variety of female voice types in the Hindi film industry which better represents how all girls sing, with the likes of Shreya Ghoshal and Monali Thakur maintaining that purity that Lataji had and others like Sunidhi Chauhan using her voice to project a more powerful image of a woman that goes with today’s times.

I had read this article maybe some 7-8 years ago and liked it immensely! It is not only very informative, but clarified to me why all those high pitch songs don’t appeal me equally, particularly those by S-J. I always loved SalilDa’s compositions and those from movie ‘Half-Ticket’ have been my favorite! I have got into music post my retirement and have joined various music groups on social network. I shared your post with some such groups who have mostly mid-aged and elders! I hope they would read it and learn something new! I shall now read your other articles too! Thank you very much!

Am not a singer. Simply interested. You mentioned the high notes Lata di and Asha di scaled, but not whether they did it in the falsetto register or not. Most likely it was high head voice. Also, Rahat and Nusrat Khan may have scaled very high notes, but I am confused as to how those would not be a falsetto, because their voice in those lines mentioned “arma ‘kayi’ ankahe..” is so all-over-the-place, broken, thinned by straining, and almost a metal genre screech. Finally, what is you opinion of a Bollywood singer who did not achieve the fame of the big ones mostly because he sung in the 80s in some “tacky” movies, not involving “trendy” or “cool” stars of that time: Mohammad Aziz. He hit high notes, Godly high notes without any hint of falsetto ever!

P.S. I keep harping on the word “falsetto” simply because they type of music that I like, its usage is ugly, awkward, gross! Even in general, I feel falsetto is an escapist technique.