Due to my upbringing in a Bengali household, I am intimately familiar with Rabindra-sangeet: the genre of songs written and composed by Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore. As a composer, artist, novelist, playwright, poet, and philosopher, Tagore has left a lasting legacy on Indian culture through his vast collection of works in a variety of mediums. Although the purism and simplicity of Tagore’s style might suggest that Bollywood is an inappropriate forum to celebrate his art, several music directors from the Golden Age of Hindi cinema have been known to use Tagore songs as inspirations for their musical compositions. The music director who is most well-known for this practice is none other than the illustrious S.D Burman. S.D. Burman is one of the most succesful music directors in the history of the Bollywood industry, and his songs from films such as Bandini (1963), Guide (1965), Jewel Thief (1967), and Aradhana (1969) are still considered all-time classics today. His filmi compositions tend to draw upon inspiration from Bengali folk traditions (e.g. bhatiaalii, saari, etc. ), but here I’d like to draw your attention to a collection of S.D. Burman compositions that are derived from Rabindra-sangeet:

meraa sundar sapnaa biit gayaa (Do Bhai, 1949): From one of S.D. Burman’s first hit scores in the Bollywood industry, this song is considered to be Geeta Dutt’s breakthrough as a playback singer in Hindi films. The mukhDaa of this song is inspired by a Bilaaval-based Tagore composition called “radono bharaa e basonto.” Geeta does an excellent job of expressing the sorrow and pain of this song with her voice, and it is truly unfortunate that the lyrics here would become a reality for her during her tumultuous marriage to Guru Dutt in the next decade.

Playback singer Geeta Dutt (1930-1972) with her husband Guru Dutt (1925-1964)

nain diivaane (Afsar, 1950): This Pilu-based composition is skilfully rendered by Suraiyya, a leading singer/actress who became a huge sensation in Bollywood during the 1940s. Bollywood as we know it today relies on actors and actresses lip-syncing songs sung by playback singers; however, in its very early days, actresses like Suraiyya used to sing their own songs for films. In spite of their dual talents, singer-actresses were not able to survive the onslaught of the Mangeshkar monopoly in the 1950s, and the playback singing paradigm became the standard that is still maintained today in the industry. In any case, this song is based on an extremely popular Tagore composition called “sediin duujane duulechhiinuu bone.” S.D. Burman literally did a copy-paste job here, as the melody of the entire Hindi song is identical to the Bengali original. While loosely basing a mukhDaa on a previous composition is somewhat acceptable, recycling a whole song written by another composer begs the question: should S.D. Burman have given credit to Tagore for this composition?

Singer/actress Suraiyya (1929-2004)

jaaye.n to jaaye.n kahaa.n? (Taxi Driver, 1954): S.D. Burman won his first Filmfare Award for Best Music Director for this song from Taxi Driver in 1954. As is often the case, the male version of the song (sung by Talat Mehmood) is more popular than the female version (sung by Lata Mangeshkar). Although S.D. Burman modified the raga of his composition to more closely resemble Jaunpuri, the first line of the mukhDaa is instantly recognizable as the main phrase from Tagore’s Bhairavi-based classic “ he khoniiker otiithhii.” Note that the Tagore original that I have provided here is sung by Hemanta Mukherjee (a.k.a Hemant Kumar), who, in addition to achieving fame as a Hindi playback singer/music director, was known for his beautiful renditions of Rabindra-sangeet in Bengali.

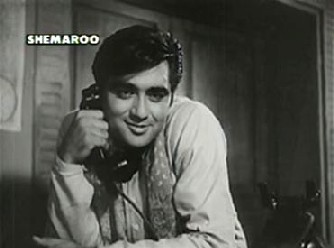

jalte hai.n jiske liye: (Sujata, 1959): This probably qualifies as my favorite “telephone song” from a Hindi film. Here, Sunil Dutt woos Nutan over the phone with this gem as he croons to Talat Mehmood’s silky vocals on playback (notice the characteristic quiver that we know and love!). Although this composition is often considered an all-time classic song of romance, fans of this song may be surprised to know that the mukhDaa is taken directly from a Tagore composition named “ekodaa tumii priye.”

Sunil Dutt serenades Nutan over the telephone with “jalte hai.n jiske liye” in Sujata (1959)

meghaa chhaye aadhii raat (Sharmilee, 1971): Out of all the compositions listed here, the inspiration from Tagore is the most difficult to hear in this song because it does not involve the mukhDaa. Rather, S.D. Burman seems to have inserted a small segment of laho laho tuule laho (0:26-0:40) into the antara of this raga Patdeep-based classic from Sharmilee. What a trickster, huh?

tere mere milan kii yeh rainaa (Abhimaan, 1973): By far, this is the most famous example where S.D. Burman has been inspired by Rabindra-sangeet. In his last hit film score (for which he won his second Filmfare Award for Best Music Director), S.D. Burman recycles the mukhDaa from Tagore’s Mishra Khamaj-based “jodii taare nai chiinii go sekii?” in this evergreen duet of Lata Mangeshkar and Kishore Kumar. Burman’s antaras are a beautiful addition to the original composition, so we won’t give him too much trouble for his rehashing of Tagore here. Note that the Bengali original that I have linked to here is sung by Kishore Kumar, another Hindi playback singer who was famous for his renditions of Rabindra-sangeet in Bengal.

Amitabh and Jaya Bacchan sing the duet “tere mere milan kii yeh raina” on stage during the climax of Abhimaan (1973).

Although S.D. Burman was often inspired by Tagore in his compositions, he never recorded or sang a single piece of Rabindra-sangeet throughout his career. The reason behind this is, of course, family feuding–an unavoidable staple of all things related to Indian culture. Here’s the story: S.D Burman’s father Nabadwip Chandra Dev Burman was set to be the direct heir to the throne of Tripura when the current king passed away in 1862. However, the crown went to Nabadwip’s paternal uncle Birchandra Dev Burman due to some dirty palace politics. Because Rabindranath Tagore had a very close relationship with Birchandra Dev Burman, S.D. Burman avoided meeting Tagore throughout his lifetime and refused to perform Rabindra-sangeet out of principle. Nevertheless, in spite of this tiff, it is undeniable that S.D. Burman had a great deal of respect for Tagore as a musician given the influence of Rabindra-sangeet on his compositions.

–Mr. 55

That was great! I love getting the gossip about the songs and inspirations for the composers creative ideas. They really do feed off of one another whether they want to or not in their closed knit community.

amazing post!

” tanSEN was bengali my dear friend, so were a lot of other people! want to see the entire list as it stands today? so was subash chandra bose and sri aurobindo :)

and i can name a million others and i am proud to say our greateness can be exerted beyond our national borders. we are the fifth largest speakers!

we bengalis have won pretty much every award in the world stage you name it we have it and we are damn proud of what we have :) its the only country in the world which took rebellion because it couldn’t speak its mother tongue and it won! and won so hard that the UN had to adopt that day as the international language day, which celebrates languages from all over the world. ”

KAMONASISH AAYUSH MAZUMDAR

MBA (2013), IMT Ghaziabad

Bengaluru, Karnataka

hometown: Kolkata, WB

in.linkedin.com/in/7thsense

Pingback: Perpetuating Gender Norms in Abhiman « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

Pingback: Bollywood’s Beloved Sopranos: Lata and Asha’s Highest Notes « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

Pingback: Roop Tera Mastana Lyrics and Translation: Let’s Learn Urdu-Hindi « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

Pingback: Which Actor Did Hemant Kumar Sing For Best? « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

Pingback: Plagiarism in Hindi Film Music: Is Imitation the Most Sincere Form of Flattery? « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

This post is incredible! Love Tagore and love SD Burman, and knew about some of the adaptations/ homages as I like to think of them, rather than lifts, as SD Burman was really adapting a very different genre into the world of Bollywood, which has its own needs and demands – but some of these links were completely new to me, like Jalte Hai Jiske Liye, one of my favorite songs from Bollywood. Also had no idea about the family feud/ politics between the royal family of Tripura and Tagore being the reason why SD Burman never recorded an actual Rabindrasangeet song. But clearly he had deep artistic respect and appreciation for Tagore as all great artists do. Politics and family history can’t get in the way of one great artist being inspired by another great artist.

Also very interesting to note that Tagore himself was ‘inspired’ by many English tunes for some of his class songs like “Puranor Shei Diner Kotha” which is inspired by Auld Lang Syne. There are countless others too.

Indeed, Tagore’s compositions reflect a combination of musical ideas from Indian classical, Bengali folk, and Western genres — this contributes to their widespread appeal!

You may also be interested in reading our post on the influence of Western music on Bollywood composers here: https://mrandmrs55.com/2012/08/24/plagiarism-in-hindi-film-music-is-imitation-the-most-sincere-form-of-flattery/

Excellently written. A few minor comments/additions:

Re: Tum na jaane kis jahaan mein – the influence that you mentioned, “Esho prano bharan”, to my knowledge, is not a Rabindrasangeet at all. AFAIK, it was writen by Pulak Bandopadhyay, and composed by Hemanta, in a very authentic Brahmosangeet style, effectively cloning Rabindranata/Jyotirindranath’s style. Given Hemant’s sub-conscuous tendency to get inlfuenced by various riffs/nuances in Tagore songs, this does sound very Rabindrik (for instance, the phrase “Jyoti purno…” could easily morph into Tagore’s “Awshoto pallabe” (the sanchari of “Saghano gahano ratri”). Since Dadar Kirti came several generations after Sazaa, this shouldn’t constitute an influence.

There were a fee other occasions where SDB mischievously used snatches from Tagore compositions, sometimes as an inside joke. Apparently, once he jocularly boasted to his musical friends that he had even ripped of the national anthem for on eof his recent hits, and challenged his bemused riends to guess which one it was. Such was the variation, that no one could fathom that what he was alluding to was the phrase “Hum ne to jab kaliyaan…” (Jaane woh kaise) which, on careful listen, would connect to the note progression of “Panjab Sindhu Gujarat Maratha”!

Another clever rip-off – the “Shei ki bhola jaaye” phrase from “Purano sei diner kothha” becomes a brief guitar bridge in “Dukhi man mere..”

There are a few others that I cannot remember right now.

Finally, I am not sure how “bhadralok” Bengalis will take to your assertion that Kishore Kumar was also “famous as a noted exponent of Rabindrasangeet”!

Thanks for your comments. I looked into it more carefully, and you are correct that “esho praan bharano” is one of the songs not written by Tagore on the Dadar Kirti soundtrack. As you said, it’s more likely a subconscious influence of Rabindra-sangeet on Hemant Kumar’s compositional style.

I wasn’t aware of the story about “jaane voh kaise,” but that is quite interesting!

As a Bengali myself, I’m certainly not afraid to praise Kishore Kumar’s renditions of Rabindra-sangeet 🙂 He’s not my favorite male artist nor am I keen on all of his musical output, but when he decided to be serious and sing Tagore’s compositions, he could really deliver. I am especially fond of his rendition of ‘ekla cholo re’ and ‘purano shei diner katha’

Ironic as it may sound, Kishore is, and has been since the time I gained musical consciousness, my favourite artist by a few light years; however, his rendition of Rabindrasangeet – outside of some brilliant stuff that he did in a few films (Charulata, Ektuku Chhoan Laage, Ghare Baire, Lookochoori…) – in the two albums that he did for Megaphone, IMHO his execution is wanting on several counts. However, that’s a separate debate not germane to the topic at hand so I will not belabour the point 🙂

Thanks again for the nice write-up.

great article.some other Tagore inspirations of Sachinda include aise toh na dekho,megha chaye aadhi raat and ye tanhaai haye haye re. by the way,bhatiali and saari are east indian (east bengali to be precise) folk tradition not north indian folk tradition as mentioned here.

Thanks for the additions. “meghaa chhaye aadhii raat” from Sharmilee (1971) is listed above as being inspired by “laho laho tule laho.”

i just listened to “yah tanhaayii haay re haay” from Tere Ghar Ke Saamne (1963), and I can tell it draws inspiration from the mukhDaa of Tagore’s “toraa je jaa boliish aamaar sonaar horiin chaay” Can you tell us the Tagore inspiration for “aise to na dekho” from Teen Deviyaan (1965)?

Pingback: Teri Bindiya Re Lyrics and Translation: Let’s Learn Urdu-Hindi « Mr. & Mrs. 55 – Classic Bollywood Revisited!

In Bengal (Bangladesh and West Bengal), a song or “gaan” for long was considered a verse expressed in the form of a tune. The verse being primary, poets from Tagore to Nazrul used tunes from various sources to express their thoughts.

Rabindra sangeets, Ekoda Tumi Preeye (1917) in the strains of Kafi and then Jodi tare nai chini go (1923) in Khamaj or Khambaj as is called in Bengal, Hey khoniker athithi (1925) in Bhairavi, Loho loho tuley loho (1925) and Rodon Bhara ei basantey (1936) in the flavours of kirtan, have often been a subject of discussion amongst music lovers as these tend to have something common with the extremely popular Hindi hits, Jalte hai jiske liye, Tere mere milan ki ye raina, jaye to jaye kahan, Megha chaya aadhi raat and Mera sundar sapna beeth gaya, all composed by Sachin Dev Burman for films.

Whether the Burman composed songs are inspired, sourced from the same material or plagiarized is a food for thought, keeping in mind that there are clear lines of demarcation between inspiration- application of folk and raaga in songs and plagiarism.

A great composer is one who returns to the opening line of a song with ease, style and flair. The opening line could be from a raaga or a folk song, the snatch of any song or a tune that a composer senses in the gentle winds of monsoon, for example, as music is everywhere for one to tap. That being the case, we find songs of similar openings. But while most are forgotton, some attain immortality, thanks to the unique progression of the songs and their return to the opening lines. The bhairavi based Jnanendra Prasad Goswami aka Jnan Goshai’s Mon bole tumi aacho bhogoban, Burman’s own Prem Jamunarey parey and Bishmadev’s Nabaruna raage are classic examples of such unique products.

The resounding success of Burman’s Hindi songs in question fall in that category; the way they took off and returned to the starting points; one marvels really at that. On the contrary, the internal musical routes, style of singing and orchestra of the corresponding Tagore songs were not adequate enough to have a firm grip in the listeners’ mind.

In course of time, when Burman’s massive hits were identified with the Tagore numbers, mind you with respect to the opening lines or a stanza, the old Rabindra sangeets were re-recorded albeit with modern approach (which in fact was more Burman like than the originals!) to find listeners acceptance. This prompted Tagore ‘bhakts’ to label Burman’s ‘gifts’ as ‘lifts’!

We, Bangalee have serious problems. We tend to look for Tagore in every phase of our lives. When Naushad composed in Malkaus, Man tarpat hari darshanko in “Baiju Bawra”, we accused him of a ‘Tagore lift’, as the song had semblance with Anando dhara bohichey bhuboney. Again, when Rajesh Roshan composed his Chhukar mere manko, we said it was Tagore’s, Tomar holo shuru, little realizing that Tagore’s piece itself was a European take!

Tagore composed 2300+ songs, Nazrul around 2,700 and if we add the songs of Rajani Kanta, DL Roy and Atul Prasad (and others), about 6,000 Bangla songs came into play during the 1881-1941 period, with the large chunk sourced from Bangla folk and Hindustani classical music. Obviously, mukhdas and antaras of many songs composed by others have in common with the works of Tagore, Nazrul etc, because of the “same raw material”.

One Tagore – SD Burman song however, is confusing though. Se din dujone composed by Tagore in 1927 while traveling by train from Bangkok to Penang and Burman’s Nain diwane sung by Suraiya in the film “Afsar” composed in 1949; both have a striking similarity throughout the song. Bishwa Bharati never objected to Burman’s use of this tune. Does it therefore mean, the tune is a traditional one from where both Tagore and Burman derived their music? Tagore sometimes used tunes “as it is’ and changed the lyrics as in the case of the Bangladesh national anthem, Amar sonar Bangla; so did Burman. Megh de paani de in “Guide” is an example, which of course sounds different from the original because of his ‘gayaki’.

In other words, the songs of interest were the trans creations of Tagore and Burman tapped from common roots and in these cases, the former was not much of a success while the latter got through with flying colours. Tagore and Burman gave us independent schools of modern Bangla music, just as we have Abdul Karim Khan, Faiyaz Khan, Allahdiya Khan and many others in Hindustani classical music.

This viewpoint is debatable. Tagore, indeed was the inspiration for all the songs that are mentioned in the main article & additions by Anindya, etc. Circumventing Tagore’s to indicate a more traditional source is a tad unfair to the genius that was Tagore (unquestionably the most influential modern music composer of this subcontinent).

As a Bengali, I would not like to self-flagellate myself by admitting that we take undue credit. 🙂 Naushad’s ‘man tadpat hari darshan’ is Malkauns, plain & simple. Tagor’s ‘aananda-dhaara bohichhey bhubaney’ sounds like a direct adaptation of a dhrupad & barring the ‘pakad’ (characteristic phrasing) of Malkauns, is a different song in mood & spirit.

However, when Naushad composes ‘o bachpan ke din bhulaa na dena’, it is only fair that we indicate the source of his inspiration to Tagore’s ‘mone rabe ki na rabe aamaare’ (& not a folk song of Wales or Scotland which may well have been Tagore’s source of inspiration).

Or when S N Tripathi, a full-fledged Bihari, composes ‘laaj bhare’ in 1946 (Film: Uttara Abhimanyu – sung by Ashok Kumar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=02dOMi3Sbc0) we must necessarily look at it as Tagore-inspired. Or when he composes songs like ‘dole meri jeevan ki naiyya’ (‘piya milan ki aas’) or ‘humein sahara ek tihaara’ (Cobra Girl), if is clear as daylight that he had Tagore in his mind.

SD’s forte was not in his ability to create ‘Tagore-styled songs’. It was different & very attractive.

Let’s not take credit away from Tagore as the most profound influencer to all composers born in the first quarter of the 20th century.

Very good article by HQ Chowdhury. This is the first time we get the inside picture of these songs.

Aidit Rahman

One song may be added , “Myay dil tu dharkan” by kishore kumar taken from Tagore’s “Promode dhalia dinu mon”

Is ‘Myay dil tu dharkan’, an SD Burman song? Which film?

HQ Chowdhury’s treatment of the subject is unique. So long, we have been hearing the same argument again and again. Sometime back someone gave an opinion and everybody seem to follow that.

Thanks HQ Chowdhury for your analysis.

Pingback: Tere Mere Milan Ki Lyrics and Translation: Let’s Learn Urdu-Hindi | Mr. & Mrs. 55 - Classic Bollywood Revisited!

jhilmil jhilmil jhiler jole bengali song sung by SD da- can anyone help and tell me which is the Hindi version of the same song? thanks Kris- pkrisp@yahoo.com

I have always had great admiration for Rabindranath Tagore. I was raised in India till I was a teen and did hear S.D. Burman’s great music too. I admire him a lot and despite tough breaks he made it I heard. I am glad you did post this article it is an eye opener for some of us interested in learning about their great skills and not some gossipy stuff.